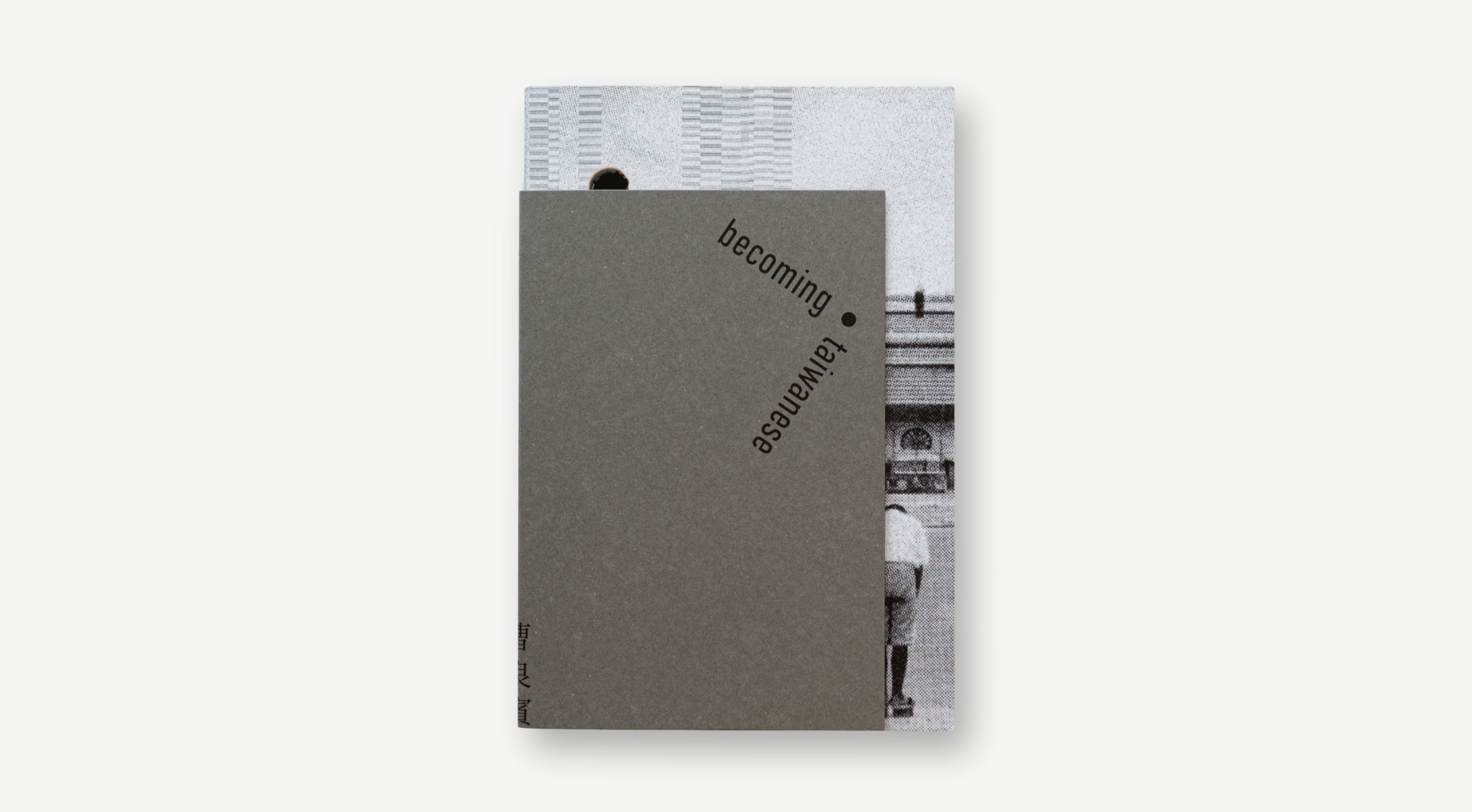

《Becoming・Taiwanese》

歷史上,台灣一直是地緣政治強權的邊陲。從鳥居到牌樓,島嶼上不同的政權更迭與族群遷徙,形塑了台灣文化的多元,也造成國族認同的分歧。

忠烈祠是台灣社會最矛盾的地景之一。它以紀念「忠烈」為名,卻建立在被拆除的神社遺址之上;它以「國家」之名進行祭祀,卻難以回應島嶼自身的歷史創傷。

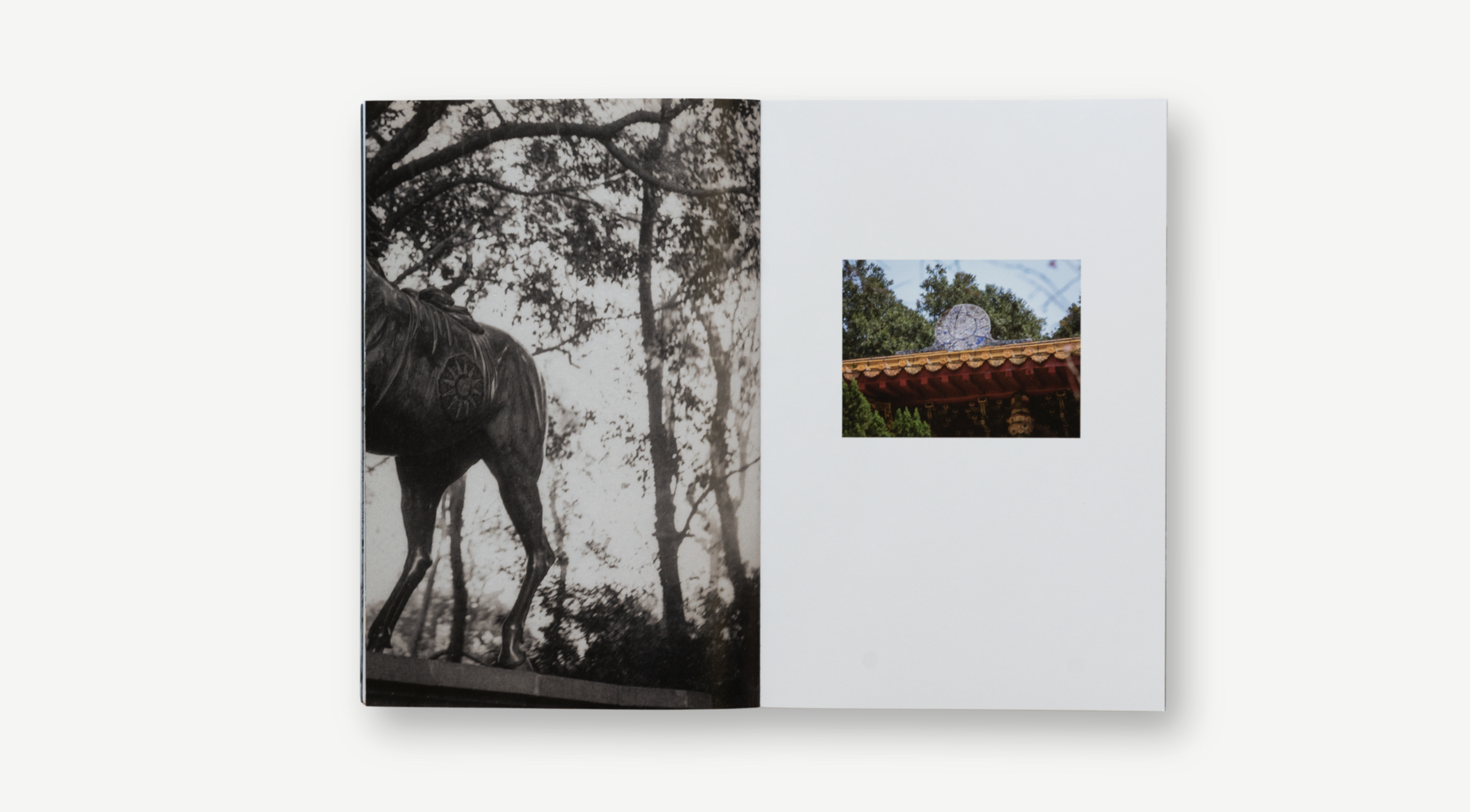

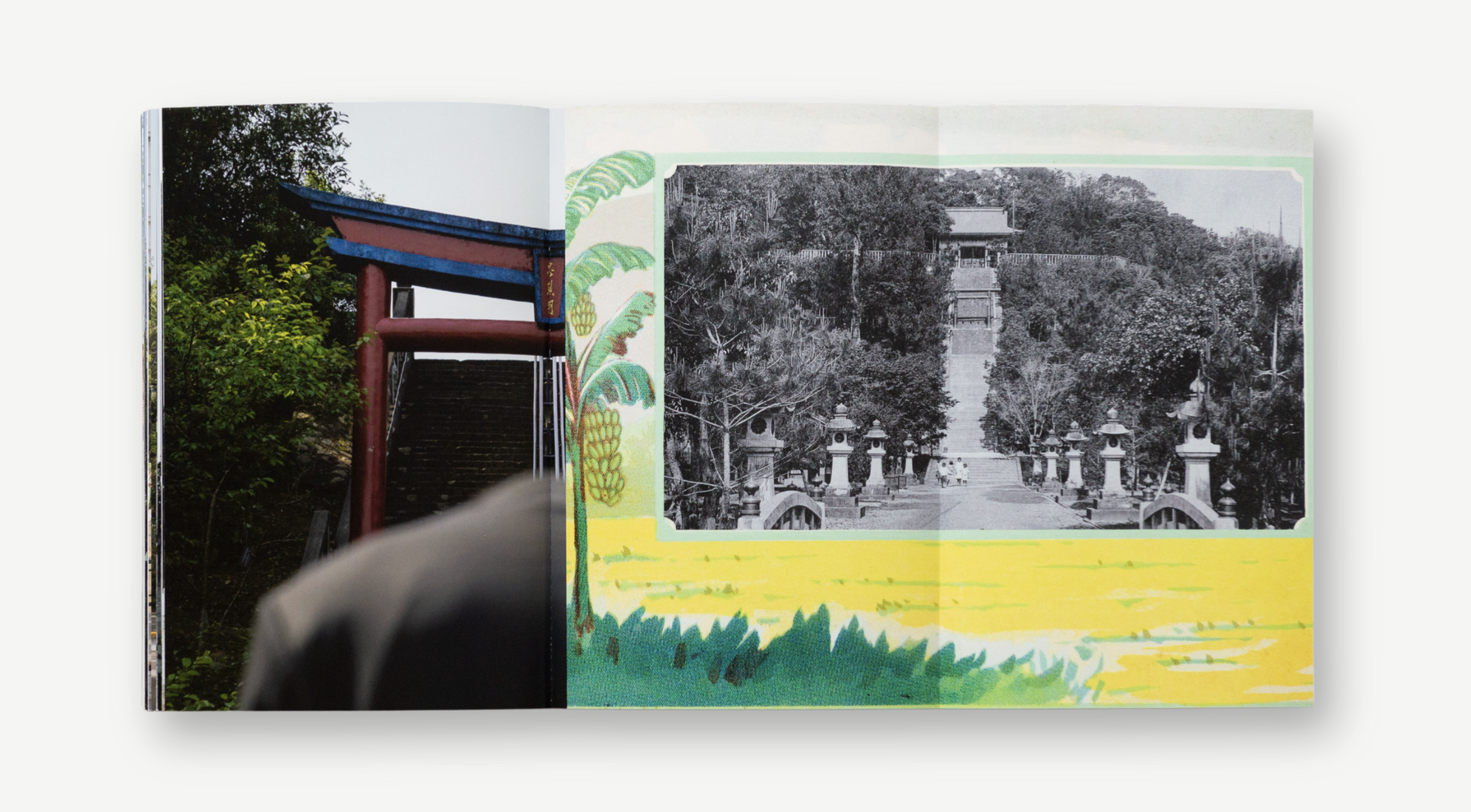

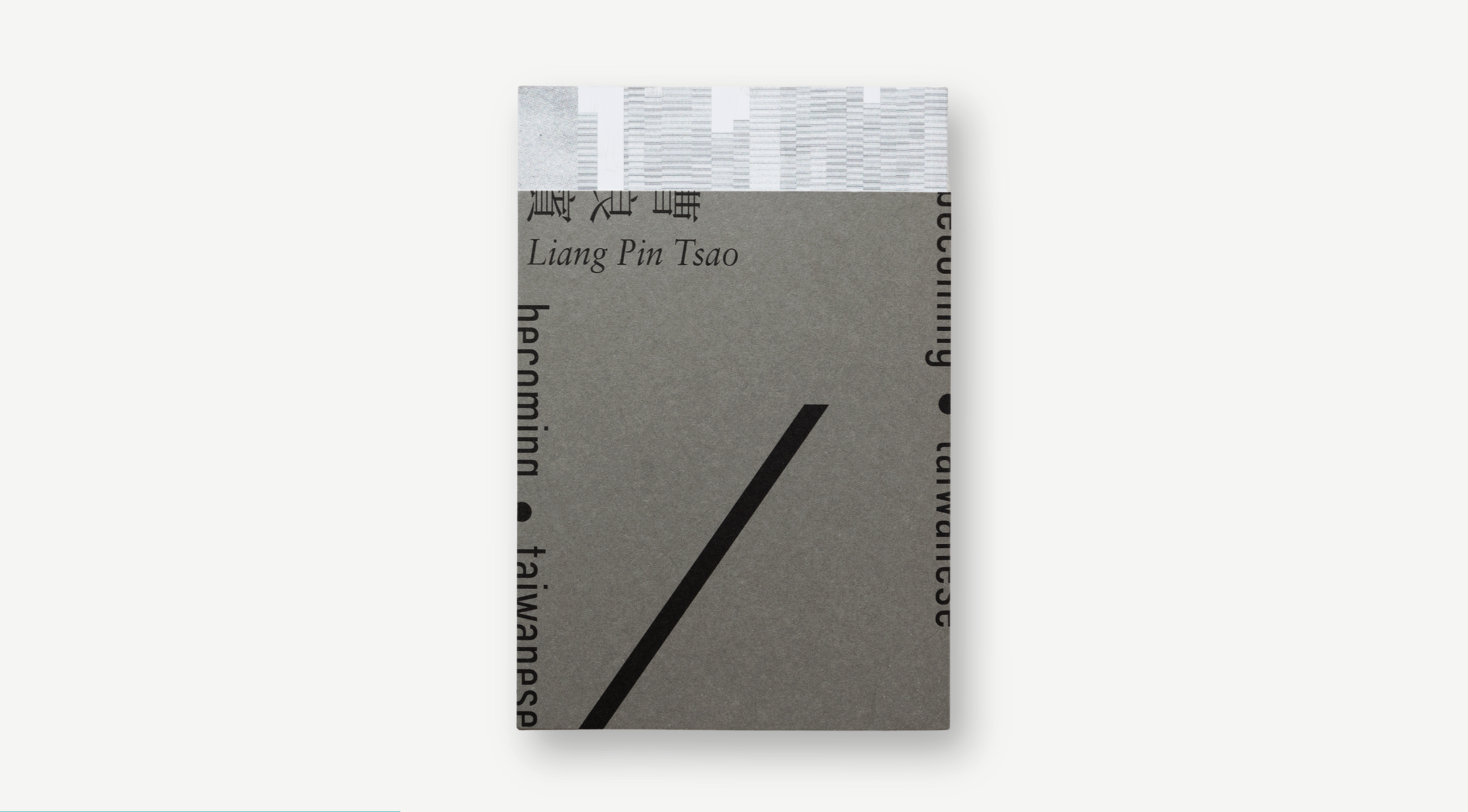

《Becoming・Taiwanese》一書中,攝影師曹良賓重新凝視這些「國殤聖域」,嘗試透過歷史影像、當代攝影與身體行為,探問亡者與生者、神聖與凡俗、專制與民主之間的關係張力,及其所蘊含的認知與情感衝突。

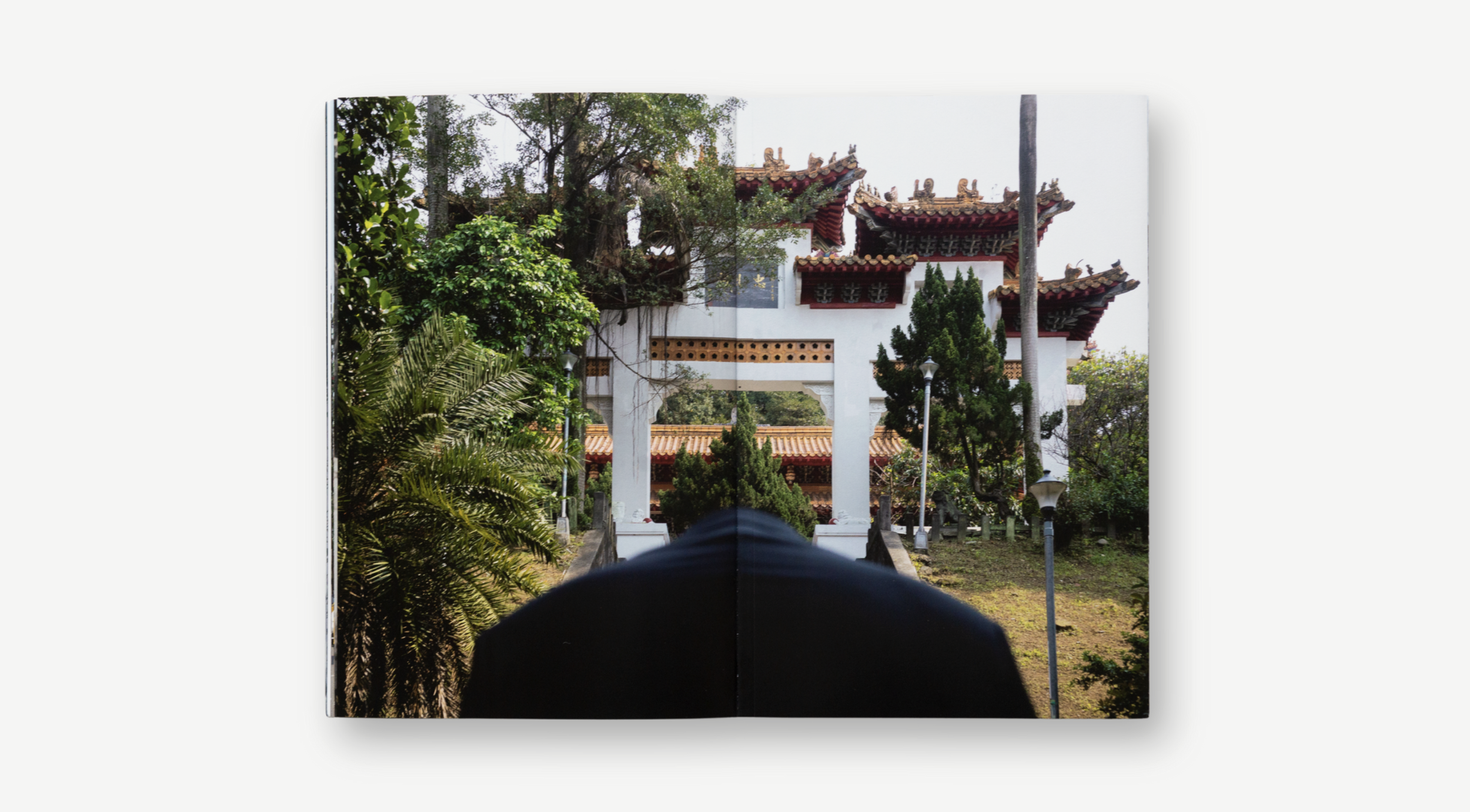

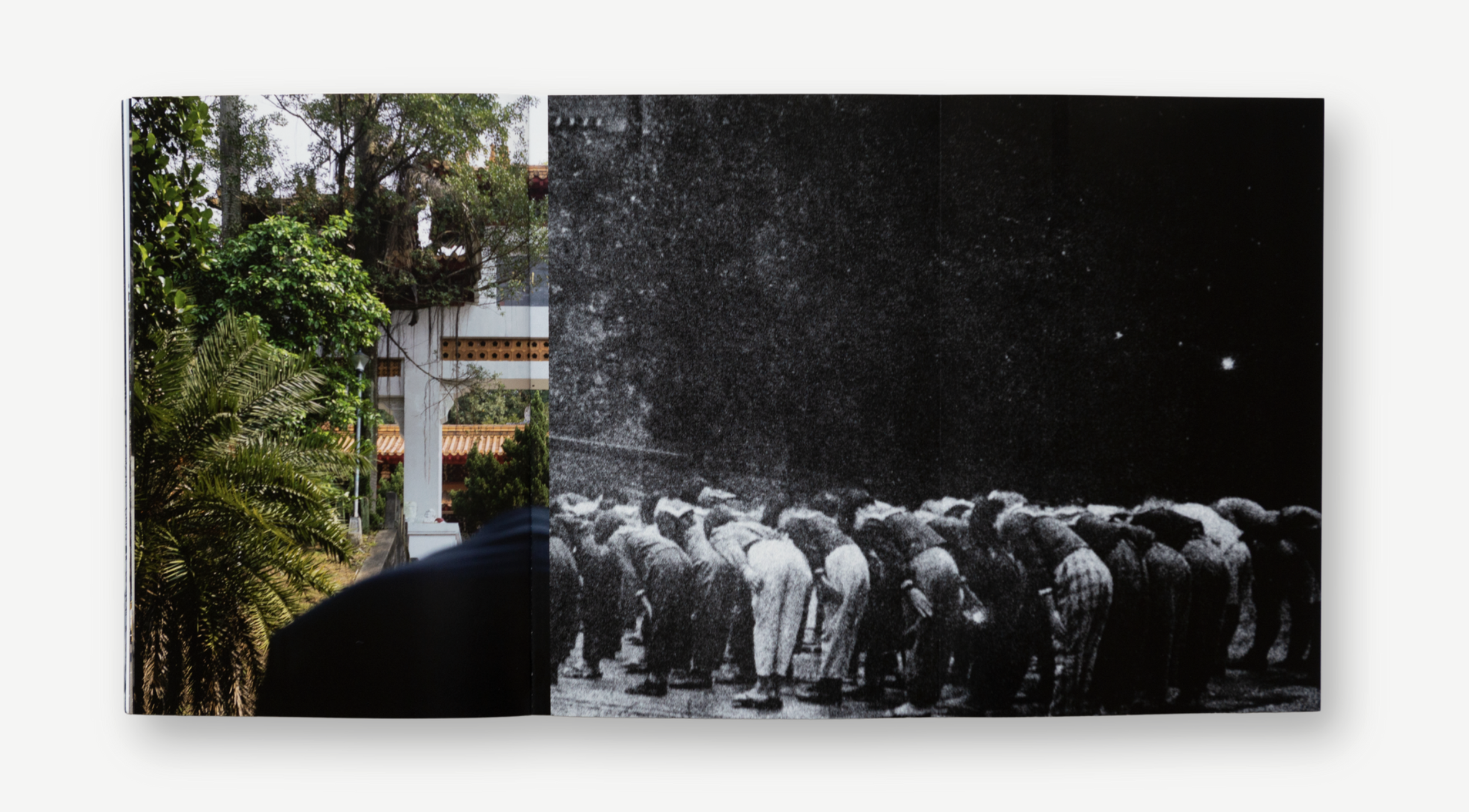

打開書本,讀者彷彿走入兩道歷史記憶的陰影:一是被殖民者強加的信仰,一是被統治者規訓的忠誠。翻開摺頁,這雙重記憶的疊影,讓忠烈祠成為了一個懸置的空間 —— 它既是紀念之地,也是失憶之所;既屬於歷史,也尚未完成,一如「成為台灣人」的意識與奮鬥過程。

1895年、日本は台湾を植民地化し、島内に200を超える神社を建立し、日本語と同化政策を推進した。1945年、国民党政権が台湾を接収すると、神社は取り壊され、忠烈祠として再建され、さらに38年に及ぶ戒厳統治が施行された。

1987年、台湾は戒厳令を解除。1991年、三大悪法が廃止され、1992年には刑法第100条の改正案が可決された。以後、台湾人は思想や言論によって罪に問われることはなくなった。

歴史の中で、台湾は常に地政学的強国の辺境に位置してきた。鳥居から牌楼へ──島における政権交替と民族移動の繰り返しが、多様な文化を育み、同時に国民的アイデンティティの分断をも生んできた。

忠烈祠は、台湾社会における最も矛盾した風景の一つである。「忠烈」を祀る名のもとに、破壊された神社の跡地に建てられ、「国家」という名の儀式を行いながらも、島自身の歴史的な傷に応えることはできない。

写真作家・曹良賓の作品集『Becoming・Taiwanese』は、これら「殉国の聖域」をあらためて見つめ直す試みである。歴史的映像、現代の写真、そして身体的行為を通して、彼は死者と生者、聖と俗、専制と民主のあいだに生じる張力を探り、その中に潜む認知と感情の葛藤を問いかける。

本を開くと、読者は二つの記憶の影の中を歩むように感じる。ひとつは植民者によって押しつけられた信仰、もうひとつは支配者によって規律づけられた忠誠。見開きページを広げると、これら二重の記憶が重なり合い、忠烈祠は宙吊りの空間として立ち現れる——そこは記憶の場であり、同時に忘却の場所でもある。それは歴史に属しながら、いまだ完成していない。まさに「台湾人になる」という意識と奮闘いの過程のように。

In 1895, Japan colonized Taiwan, establishing more than two hundred Shinto shrines across the island and enforcing a policy of linguistic and cultural assimilation. In 1945, after the Nationalist regime took over Taiwan, the government demolished the shrines, rebuilt them as Martyrs’ Shrines, and imposed martial law that lasted thirty-eight years.

In 1987, martial law was lifted. In 1991, the three major repressive laws were abolished. In 1992, an amendment to Article 100 of the Criminal Code was passed, putting an end to the prosecution of Taiwanese people for their thoughts and speech.

Historically, Taiwan has always been a frontier of geopolitical powers. From torii to pailou, successive regimes and waves of migration have shaped the island’s cultural diversity, while also deepening its divisions over national identity.

The Martyrs’ Shrine is one of Taiwan’s most conflicted landscapes. It claims to honor the “loyal and the brave,” yet it rises upon the ruins of the shrines it destroyed. It prays in the name of the nation, yet struggles to confront the island’s own historical trauma.

In Becoming・Taiwanese, photographer Liang-Pin Tsao revisits these “sacred sites of national mourning,” using archival images, contemporary photography, and performative gestures to question the relational tension between the dead and the living, the sacred and the profane, autocracy and democracy, and the cognitive and emotional conflicts embedded within.

As the book unfolds, readers step into the overlapping shadows of two memories: one of faith imposed by colonizers, the other of loyalty disciplined by rulers. When the foldout opens, the overlapping of these dual memories renders the Martyrs’ Shrine a suspended space — at once a site of remembrance and of forgetting, belonging to history yet still unfinished, much like the ongoing process of becoming Taiwanese.

Moom Bookshop:書籍簡介|書籍紹介|Book description & Purchase link